"As long as the game endures, it will bow in silent tribute to William John Hebert and others like him who have died in order that we might live in freedom."

The Sporting News, November 19, 1942

William J. "Billy" Hebert was born in Stockton, California on December 20, 1919 - the only child of Mr and Mrs George Hebert. The scrappy little infielder's diamond talents were first showcased with the Karl Ross post American Legion team. In 1936, his final year in American Legion ball he captained the team.

Hebert was a confident young man who believed in his abilities, and despite being only 16 he managed to convince San Francisco Seals' manager Lefty O'Doul to give him a tryout. Although Hebert was told to come back after he graduated from high school he made a favorable impression. "I saw a kid today who will make a star some day," Seals' publicist and former major league pitcher Walter Mails told the San Francisco Examiner after Hebert's tryout.

In the winter of 1937, Hebert traveled to San Francisco to play in the Seals Stadium League - a high level semi-pro league that played on Sundays and featured many players with professional experience. Hebert played second base and led off for the Dan P Maher club, a team sponsored by a local paint company. "I never saw a ball player who had such a dirty uniform," recalled Pete Deas, the team's shortstop, in an interview with baseball author Tony Salin. "He chewed tobacco and he'd spit tobacco juice on his hands and rub it on the front of his uniform. He always seemed to be sliding into a base or diving for a ground ball. He was one of the first guys I ever saw who would slide head-first into a base."

Hebert had an impressive season and in 1939 Cincinnati Reds' scout Bob Grogan signed him to a professional contract. He was to get $75 a month. The second baseman was assigned to the Ogden Reds of the Pioneer League where fellow middle-infielder Pete Deas from the Dan P Maher team would also play. "We were a good combination," Deas told Salin. "We worked well together - double plays, force plays, who would cover second on steals, things like that."

The home opener for Ogden was a 26-15 pounding of Salt Lake City. Hebert was 4-for-6 that day with a triple and a grand slam. He finished the year with a .302 batting average and 52 RBIs. "We had a friendly bet about who would have the highest batting average," Deas explained to Tony Salin. "I hit .300. So I paid him the money." The bet was for one dollar.

In 1940 Billy Hebert's contract was picked up by the Oakland Oaks. He played through spring training but was released before the season began. He did not play orgainized baseball in 1940 but found time to fall in love and get married. Hebert would be divorced before he entered military service.

Hebert was signed by the Merced Bears of the California League for the 1941 season. He had an exceptional year batting .328 in 130 games to lead the team. He led the league in double plays by second basemen and a bright future in baseball seemed to be on the horizon for the 21-year-old.

But shortly after the season ended Hebert entered military service. Like his father, Billy Hebert was a metalsmith, and this was a trade urgently needed by the armed forces. Hebert joined the Navy and trained at the Naval Air Station in Alameda, California before moving on to the Naval Air Station at Norfolk, Virginia. On July 14, 1942, Aviation Metalsmith Third Class (AM3C) Hebert left for the Pacific.

Guadalcanal is situated in the middle of the long Solomon Islands chain, northeast of Australia. The location of the Solomons made them key to Japanese plans for cutting off shipping between the United States and Australia. In 1942 the Japanese started occupying all of the islands, Guadalcanal was to be a major air base that would constantly threaten Allied shipping. The Allies, aware of the Japanese plans, decided to occupy Guadalcanal first and a muddy airstrip was captured from unarmed Japanese construction workers and renamed Henderson Field. The airfield would be the main focus of the Guadalcanal campaign.

AM3C Hebert was assigned to Henderson Field to help keep Naval airplanes serviceable. It was a dangerous place to be and repeatedly came under attack from the Japanese. When the battleships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, Kongo and Haruna, bombarded Henderson Field the night of October 13/14, their 14-inch shells all but destroyed the place and most of its airplanes. It was probably during this bombardment that Billy Hebert sustained the injuries from which he died on October 21, 1942.

"The Stockton, Cal., lad won't answer the umpire's call when it sounds again throughout the land," wrote The Sporting News on November 19. "But his memory will be cherished long in the annals of the game as the first to lay down his life so that both his country and the sport to which he dedicated himself might survive."

Many were saddened by the death of Hebert. "I was in Milne Bay, New Guinea, during the war when I heard he'd died," says his former double play partner Pete Deas. "Mother and Dad sent me the clipping. They figured I'd want to know. It was a shock. Very sad."

Frank Enright, a boyhood friend of Hebert's, was in North Africa serving as a private in the Army engineers when he heard the news. He sent a letter to the Stockton Record.

"Billy Hebert is the kind of man who should be remembered at home. I would like to see a plaque erected in his memory at Oak Park where he played so many Legion ball games. I am enclosing $10 to start the ball rolling. I would make it more only I haven't got it."

Another friend, Dario Bella, serving with the Navy at Farragut, Idaho, added $5 and soon the sports commission of the Stockton Chamber of Commerce organized a drive to erect a flagpole and bronze memorial tablet in centerfield at Oak Park in honor of Hebert. The Chamber encouraged $1 donations from friends to fund the $250 project. Within a few weeks they had more than $700.

On Memorial Day, May 30, 1943, in a moving ceremony, the flag was raised on a new flagpole in centerfield at the Oak Park ballpark to the sound of the Army Air Force band from Stockton Field. A bronze plaque, lovingly crafted by Billy's father, was unveiled at the base of the flagpole. "It will remain as a permanent record of a war hero's sacrifice," wrote John Peri, the Stockton Record's sports editor. The ceremony was followed by a game between Hebert's old American Legion post team, Karl Ross and the Bill Erwin post team from Oakland.

In 1951, Oak Park was renamed Billy Hebert Field. It burned down two years later and the new ball park, still called Billy Hebert Field, is the one that stands today in the grounds of Oak Park. But in 1967, when the fences were moved in, the memorial to Hebert was hidden - 24 years after Hebert's death no-one really noticed. Not until 1992, when two of Hebert's old friends, Joe Souza and Rab Longacre discovered the plaque overgrown by weeds did a new drive start to have it relocated. On November 11, that year, the plaque George Hebert had inscribed for his dead son was relocated in front of the grandstand.

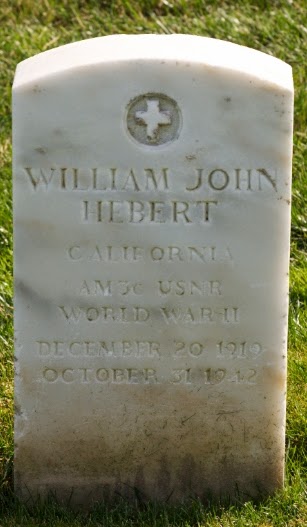

Billy Hebert, the first professional baseball player to be killed in WWII, is buried at the Golden Gate National Cemetery in San Bruno, California.

No comments:

Post a Comment